Most horse owners around the world, whether they own a champion sport horse or a humble pet pony, will have discussed parasite treatment with their vet as part of their animal’s health plan. While dealing with some internal and external parasites is a normal part of equine life, gastrointestinal parasites (often referred to as worms) that hitch a ride inside a horse’s digestive tract can cause significant health and performance issues. The parasites’ eggs are generally shed in the animal’s faeces, where the hatched larvae migrate and later get ingested by a new host. Several factors, such as a horse’s age, body condition, stress levels and even its gut microbiome (the bacteria living within the digestive tract), can influence how well an animal may tolerate an infection. In addition, season, pasture management and deworming practices can affect the parasite type and infection level. Here is what you need to know about these worms and how they impact your horse’s health.

While research has shown that mild levels of parasitism can be good training for the immune system in mammals [1], when infections get out of control or affect immuno-compromised horses, they can cause significant issues. Dehydration and insufficient nutrient uptake caused by diarrhoea are likely to affect athletic performance in sports horses and the physical development of foals and young stock. As physical condition and nutritional status can have knock-on effects on reproductive ability, infections may also affect the breeding performance of mares and stallions. Poor body condition stemming from intense parasitism has been associated with ovarian inactivity, a leading cause of infertility in breeding mares [2]. Symptoms such as lethargy will particularly affect the training and competition success of sport horses, while a dull coat and poor body condition can reduce a show horse’s chances in the show ring. Other signs of infection include increased flatulence, coughing, weight loss, and a pot belly. In the most severe cases, colic can develop and lead to death. Even in the absence of clinical signs, internal damage can occur. Some parasites migrate through other organs, such as the lungs and liver, before arriving at the digestive tract and cause substantial damage during their migration.

Ascarid (roundworm) larvae can cause lung airway inflammation, often accompanied by nasal discharge and an increased respiratory rate [3]. This can lead to haemorrhaging of the lungs in athletic horses and pneumonia in foals. In the gut, they can obstruct the passage of food and lead to colic.

Large strongyles penetrate the bowel lining and travel through various arteries that supply the digestive tract. Anaemia can result, and if severe infections occur, colic may develop as a portion of the intestine is starved of blood supply. Small strongyle larvae migrate to and hibernate in the gut wall. As they emerge from hibernation, they can cause substantial damage to the gut wall as they exit it.

Strongyloides westeri (threadworm) is commonly found in foals under two months of age. Foals eventually develop immunity to this parasite, but early-life infection can lead to diarrhoea, dehydration and poor growth from reduced nutrient uptake. As it can be transmitted through the mare’s milk, it is a parasite of particular importance to breeders.

While previously thought not to be associated with colic, tapeworm infections are now a known causative agent of colic. During active infection, these parasites damage the intestinal lining and cause nerve degeneration at their attachment site. They can also obstruct the bowel and lead to intestinal rupture. Tapeworm eggs do not always appear in faeces, but saliva and blood tests are available to confirm infection if suspected.

Both grazing and stabled horses are at risk from ingesting the larvae that hatch and migrate from parasite eggs shed in faeces. Ascarid eggs can live freely in the environment for up to eight years and are notoriously sticky. They will adhere to buckets, licks and boots, allowing easy transmission between paddocks and stables. Strategies for lowering the risk of parasite-induced health issues include regularly clearing pastures of faeces and rotating animals between paddocks to reduce exposure. A recent study from Clermont Auvergne University, France, also showed that co-grazing horses with cattle reduced strongyle eggs in faeces by 50% compared to equine-only pastures [4]. Special additions to a horse’s diet may also be helpful, as students from Moate Community School, Co. Westmeath, recently demonstrated. They created a herbal horse treat containing Slippery Elm, Fennel, Thyme and Mint that reduced the number of parasite eggs observed in faeces [5].

Historically, the most practised control measure has been the routine treatment of horses with anthelmintic drugs (wormers) at specific times of the year, most commonly around spring and autumn. However, treating all animals twice a year in this manner has given parasites a chance to adapt. As a result, parasitic resistance to well-known wormers has become a significant issue. The 80:20 concept that 80% of parasite eggs are shed by 20% of the herd has led to an alternative approach to deworming whereby only the highest egg-shedding animals (and those in clear need of medical attention) are treated [6]. This helps to maintain non-resistant worm populations in untreated horses and better preserves the efficacy of available drugs.

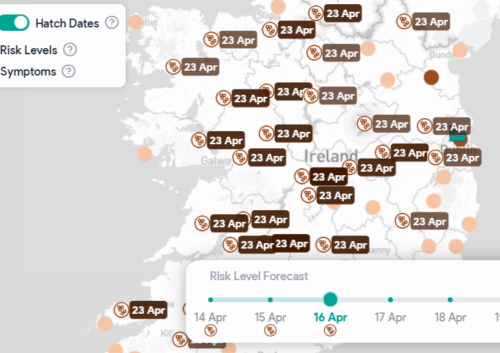

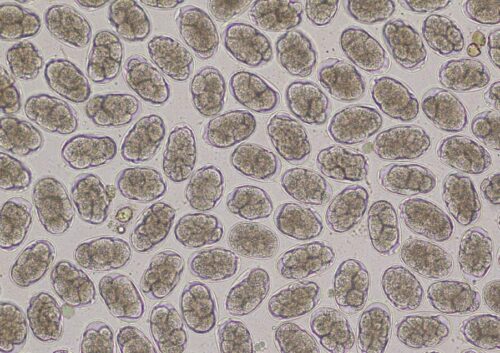

Monitoring your horse for the presence of gastrointestinal parasites and estimating their burden level can be largely achieved by faecal egg count (FEC) testing. FECs can provide information on what parasites are present and help owners and vets choose the most effective wormer. Additionally, they can indicate which horses shed the most eggs so that egg shedding and exposure to larvae can be better controlled within the herd. Routine monitoring through FECs is a valuable and essential tool that can help owners to keep track of the effectiveness of their husbandry decisions, help vets, together with clinical symptoms, to devise a treatment plan and evaluate the efficacy of administered wormers.

References:

- Galaxy advanced microbial diagnostics. Retrieved from: https://www.galaxydx.com/parasites-and-the-immune-system/

- Ali, A., Alamaary, M., & Al-Sobayil, F. (2021). Clinical and laboratory findings in barren Arabian mares. Comparative Clinical Pathology, 30(1), 35-40.

- Clayton, H. M., & Duncan, J. L. (1978). Clinical signs associated with Parascaris equorum infection in worm-free pony foals and yearlings. Veterinary Parasitology, 4(1), 69-78.

- Forteau, L., Dumont, B., Salle, G., Bigot, G., & Fleurance, G. (2020). Horses grazing with cattle have reduced strongyle egg count due to the dilution effect and increased reliance on macrocyclic lactones in mixed farms. animal, 14(5), 1076-1082.

- Teagasc (2023). Retrieved from: https://www.teagasc.ie/news–events/news/2023/btyste-2023.php

- Westgate labs. Retrieved from: https://www.westgatelabs.co.uk/info-zone/management-tips/6-ways-to-better-worm-control-in-competition-horses/