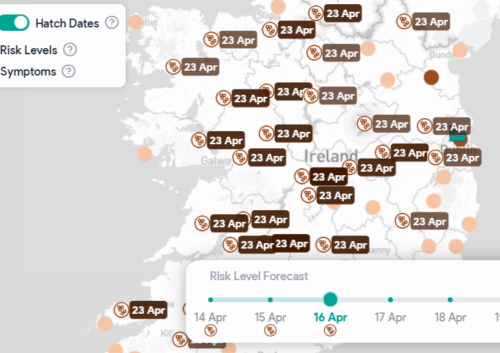

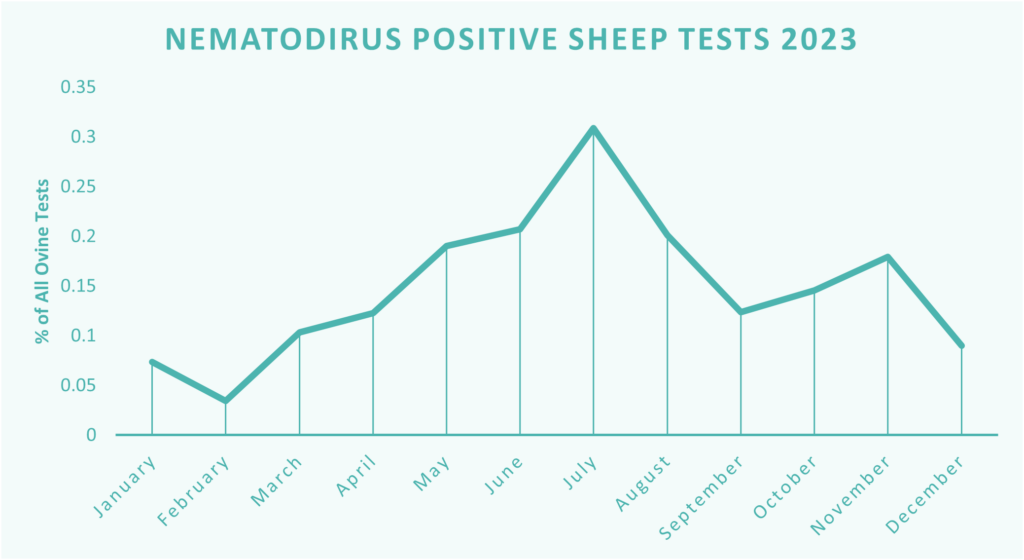

The arrival of spring may bring a thought of newborn lambs frolicking on the fields but danger lurks waiting for warmer weather to surface. Nematodirus is a parasitic roundworm that affects sheep, particularly lambs, goats, and occasionally cattle. Despite the expectation of little to no infection risk during colder winter months, this may not be the case. For instance, Micron 2023 test data identified a notable 7% sample positivity for Nematodirus of all ovine tests in January and 9% in December! (Figure 1) Understanding why there is a prevalence in Nematodirus-positive samples is important for effective management and prevention strategies.

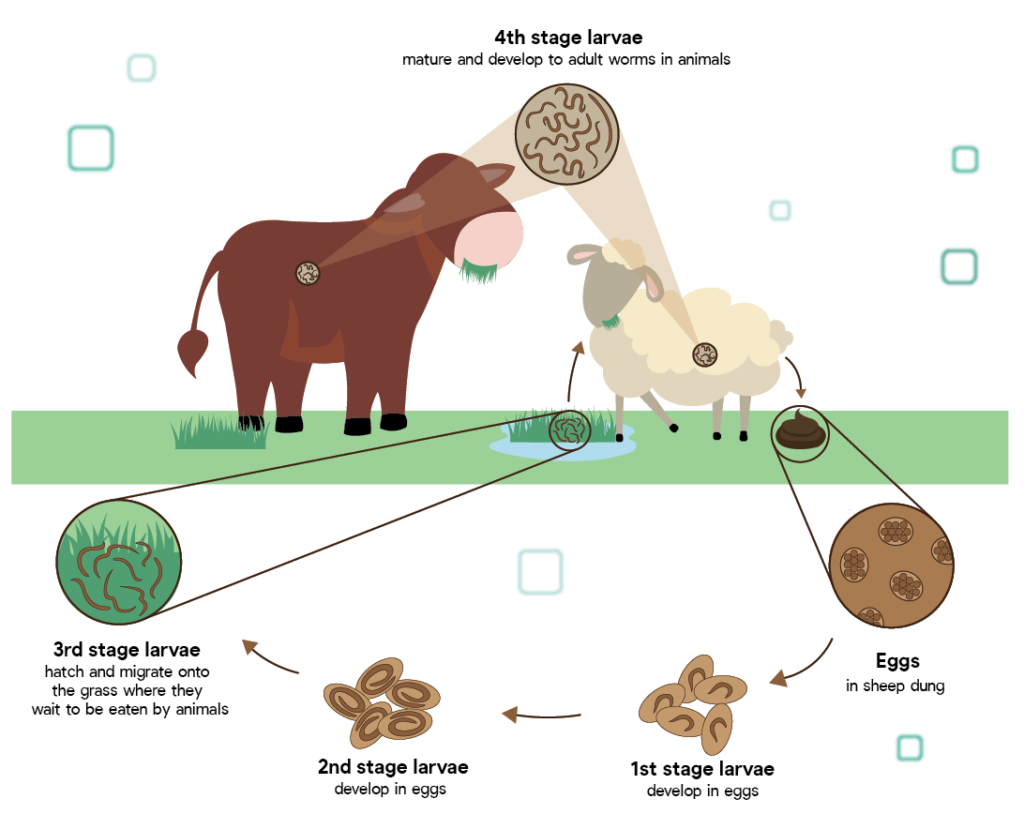

Life cycle

The life cycle of Nematodirus begins with the release of eggs within the host faeces onto the pasture. The eggs can remain viable in the soil even under harsh weather conditions, such as cold temperatures. In contrast to other parasitic worms with free-living stages, Nematodirus early larval stages develop within the egg itself. Under favourable weather conditions (cold weather followed by ≥10°C temperatures), first-stage larvae (L1) develop within the eggs. This is followed by the development of second-stage larvae (L2) and third-stage larvae (L3). The free-living stages can occur over a period of weeks to months as the larvae can remain dormant until conditions are suitable to hatch. The L3 larvae are the infective stage and migrate onto herbage in search of a host. The ingested L3 larvae move to the intestinal lining where they develop into fourth-stage larvae (L4), eventually becoming egg-producing adult worms. Large numbers of L3 larvae are the main cause of damage as they disrupt the mucosa of the small intestine affecting absorption, and causing protein loss, severe watery diarrhoea, dehydration and weight loss.

Environmental factors

Temperature and humidity are environmental factors that can impact Nematodirus. Climate change has led to warmer winters and prolonged periods of favourable conditions for parasite development. Warmer temperatures provide ideal conditions for egg hatching and larvae survival and can shorten the development cycle of Nematodirus, meaning more larvae are able to develop and infect more sheep at a quicker rate.

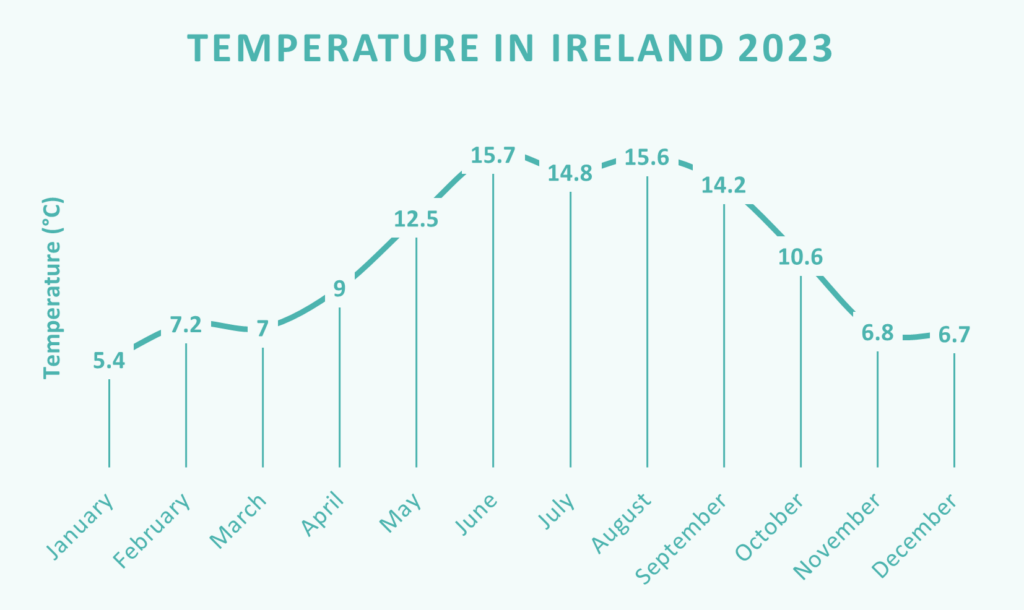

Considering the percentage of Nematodirus-positive tests (Figure 1) with the monthly temperature (°C) figures in Ireland (Figure 3), a positive correlation is evident between temperature and Nematodirus-positive tests. As the temperature rises, so too does the proportion of Nematodirus-positive tests. This reflects the requirement of warm temperatures for the developmental cycle from egg to infective larvae.

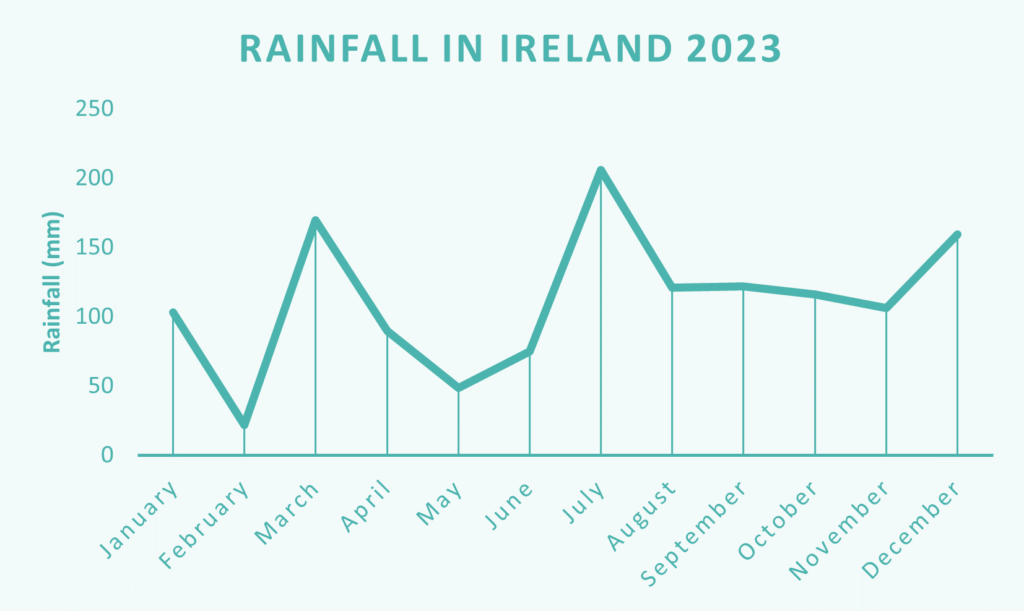

Changes in light and rainfall also have an impact on the life cycle and overall survival of Nematodirus. Nematodirus functions best at higher humidity and rainfall levels. These favourable conditions prevent the larvae from drying out and dehydrating, as well as speeding up the egg hatching process. Due to the higher survival rate and increased hatching, more larvae can be found on pasture leading to a greater risk of infection in livestock. Emergence of larvae from dung and some movement of larvae occurs through water levels on pasture. Therefore, higher moisture levels can disperse the larvae throughout the pasture across grazing areas, increasing infection risk.

Considering the percentage of Nematodirus-positive tests (Figure 1) with the monthly rainfall (mm) figures in Ireland (Figure 4), a higher proportion of Nematodirus-positive tests is evident following or during a period of heavy rainfall with exceptions during periods of cold spells (Figure 3). A combination of warm temperature and above average rainfall contributes to increased survival and infection rates of Nematodirus.

Met Éireann 2041-2060 weather projections showcase an increase of 1–1.6°C in mean annual temperatures, with highest day temperatures projected to rise by 0.7–2.6°C in summer and lowest night temperatures to rise by 1.1–3°C in winter. The frequency of heavy precipitation events is projected to increase by approximately 20% during winter and autumn months. This projected increase in mean temperatures and rainfall as a result of climate change facilitates the survival and development of Nematodirus.

FECs and treatment

Faecal egg counts (FECs) facilitate informed treatment decisions, guiding the choice of appropriate anthelmintic. As the damage to the intestines is caused by the larvae and not the egg-producing adults, FECs are not a reliable form of diagnosis in individuals as damage is often done before the pre-patent period is complete. However, FECs are useful for indicating pasture burden levels for subsequent lambing seasons. Additionally, FEC reduction tests can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a drug by conducting FECs before and after administering a drug.

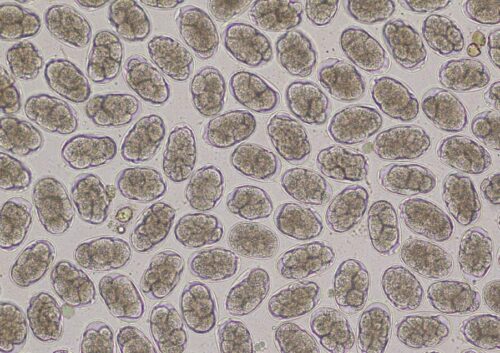

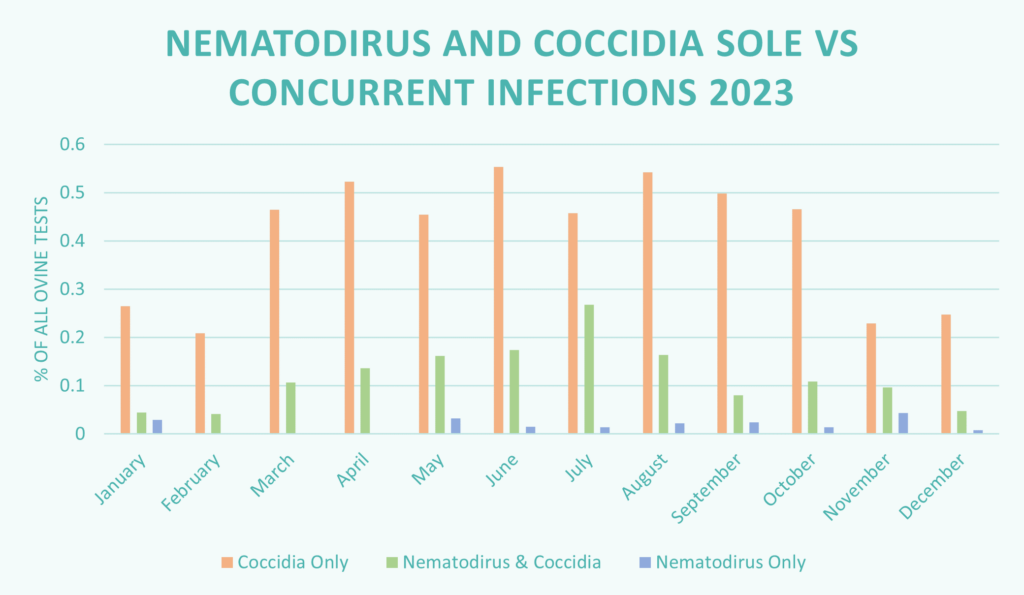

Along with Nematodirus, another major parasitic challenge a young lamb will face is infection with coccidia. Coccidia occurs at a similar age and stage of the year as Nematodirus meaning that lambs can suffer from a concurrent infection with both parasites at the same time. A concurrent infection can be worrying for a young animal as these parasites can have immediate and long-lasting effects. These animals may be unable to acquire nutrients and damage can be fatal in severe cases. Micron test data 2023 showcased a greater proportion of concurrent infections with Nematodirus and coccidia than Nematodirus only infections in ruminants consistently throughout the year (Figure 5). Faecal testing is not recommended for these parasites in young animals and treatment decisions should account for clinical signs, timing and farm history.

Treatment plans should be tailored to ensure the right anthelmintic is used for the intended target. For Nematodirus, a benzimidazole based product (white drench) is a good choice in lambs, to preserve the efficacy of other drugs further on in the season. A second treatment may be required as lambs can become re-infected, especially when grazing in a mixed-age grouping system.

In conclusion, understanding the lifecycle and environmental factors influencing Nematodirus prevalence is important for effective management and prevention strategies. Recent data challenges the pattern of low infection risk in colder months. The survival of Nematodirus eggs through harsh conditions generates difficulty in removing infection risk. Environmental factors, such as temperature, humidity, and light influence the development, survival, and distribution of Nematodirus.

With the ever-changing environmental conditions, using FECs can help to predict pasture contamination levels, which alongside robust treatment plans assist in reducing infection.

References & useful resources

- Aleuy, O.A. and Kutz, S., 2020. Adaptations, life-history traits and ecological mechanisms of parasites to survive extremes and environmental unpredictability in the face of climate change. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife, 12, pp.308-317.

- Farm Health Online. ‘Nematodirus battus’ https://www.farmhealthonline.com/disease-management/sheep-diseases/nematodirus/

- Melville, L.A., Van Dijk, J., Mitchell, S., Innocent, G. and Bartley, D.J., 2020. Variation in hatching responses of Nematodirus battus eggs to temperature experiences. Parasites & vectors, 13, pp.1-8.

- Melville, L.A., Innocent, G., Van Dijk, J., Mitchell, S. and Bartley, D.J., 2024. Refugia, climatic conditions and farm management factors as drivers of adaptation in Nematodirus battus populations. Veterinary Parasitology, 327, p.110120.

- Met Éireann. ‘Monthly Data – Mount Dillon’ https://www.met.ie/climate/available-data/monthly-data

- SCOPS. ‘Nematodirus in Lambs’ https://www.scops.org.uk/internal-parasites/worms/nematodirus-in-lambs/

- Teagasc. ‘Nematodirus and coccidia in young lambs’ https://www.teagasc.ie/news–events/daily/sheep/nematodirus-and-coccidia-in-young-lambs-.php

- Van Dijk, J. and Morgan, E.R., 2012. The influence of water and humidity on the hatching of Nematodirus battus eggs. Journal of helminthology, 86(3), pp.287-292.