Whilst warmer weather and sunny afternoons might seem a distant memory, now is the perfect time to plan for regular testing over the coming months.

A parasite is defined as an organism that lives in or on an organism of another species (the host), deriving nutrients at the other’s expense. Gastro-intestinal parasites cause a broad range of symptoms which vary depending on the species involved, many of which are non-specific. It is possible to have infections without any symptoms if the burden level is low (sub-clinical), or even a negative faecal test despite infection if the parasite has not yet reached maturity. Staying vigilant for signs of diarrhoea, lethargy, weight loss and general ill-thrift can help identify animals that might be facing a parasitic challenge.

Performing a good test

Faecal egg counts provide great insight into infection status of animals, pasture contamination levels, and allow for more informed treatment decisions. Getting the most from your testing involves good sample collection and preparation – but what do your test results mean?

EPG Result

When a faecal sample is tested, only a small amount (3g) will be used for analysis. During the preparation phase, samples are combined with water to help break the faeces up – but this dilutes the sample before it goes into the testing slide. To counter this, when eggs are seen in the chamber the total is scaled-up based on the known dilution factor and slide dimensions to provide your result in eggs-per-gram (EPG). Your result will be returned showing the EPG count for the different worm types that affect the animal species selected during the test set-up.

Know your worms

Micron Kit identifies eggs, and categorises the results into the following groups (depending on the species selected):

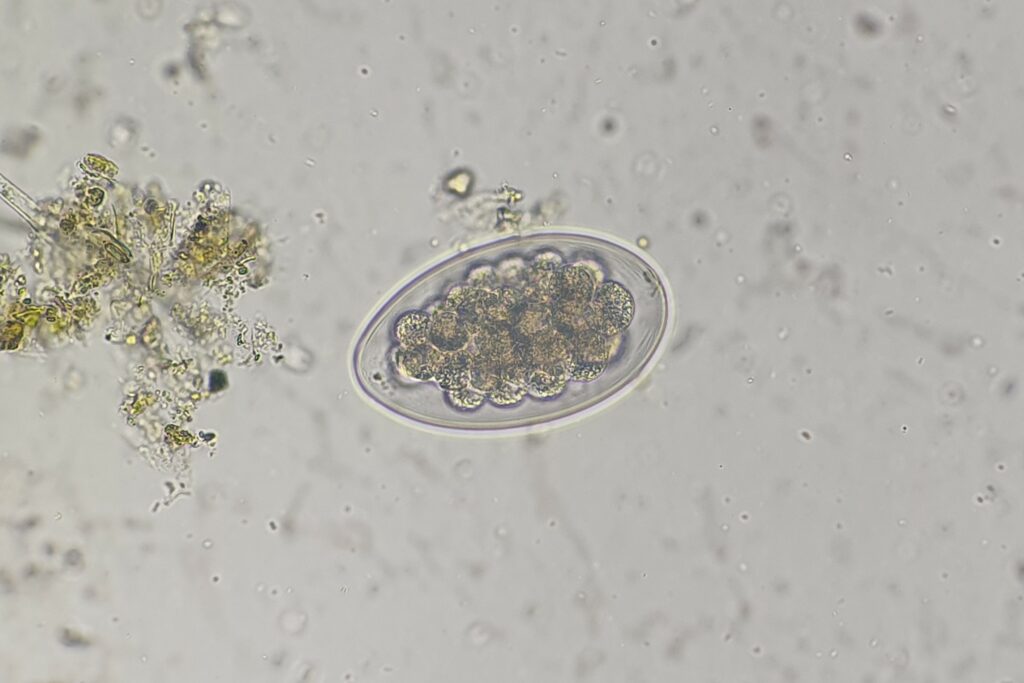

Strongyles

- ‘Strongyles’ seen in the test refer to nematodes of the Strongylidae family, and include worms such as Haemonchus, Ostertagia, and Cooperia.

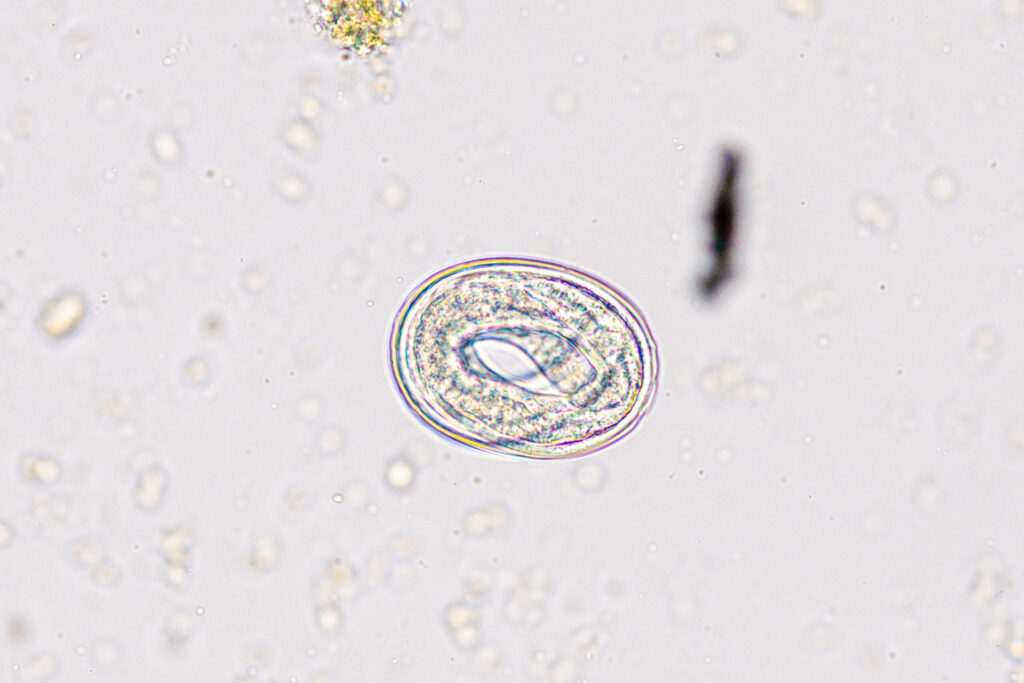

- Eggs seen in the slide cannot be speciated by visual examination alone. Additional larval culture is needed to determine which species is present.

- Some strongyles can encyst within the host, avoiding treatment with certain medications.

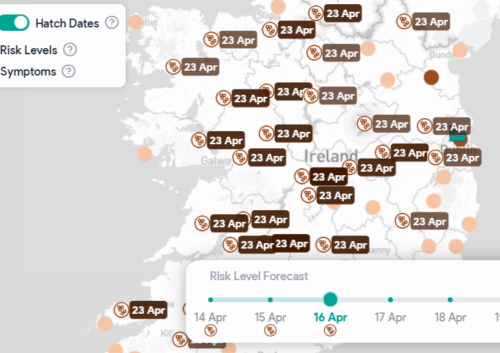

Nematodirus

- Inhabit the small intestine of ruminants, and are particularly significant in lambs.

- Larvae develop within the egg, but require a period of cold weather followed by a warm spell before they are able to hatch. Mass-hatching of overwintered eggs provides a threat at pasture.

- Mechanical damage to the lining of the intestine is caused by the larvae, not adult worms. This can lead to diarrhoea, weight loss, or even death if left unchecked.

Strongyloides

- Threadworms of the small intestine.

- Disease often occurs in younger animals but is not usually of significant economic importance.

- Neonates may acquire infection when taking milk from infected mothers.

Moniezia

- Cestode infections in ruminants are usually asymptomatic but may cause failure to thrive.

- As with equine tapeworm, they require free-living oribatid mites to complete their life cycle.

- Eggs are round or triangular shaped with thick outer membranes.

Trichuris

- Whipworms often occur after hot, dry conditions have reduced the pasture contamination of other parasites.

- Adults are found in the large intestine, producing eggs that are very environmentally resistant.

- Trichuris eggs are lemon-shaped with distinctive plugs at each end.

Anoplocephala (Equine)

- Equine tapeworms require oribatid mites to complete their lifecycle, making grazing horses at higher risk of acquiring this parasite.

- Most infections do not cause clinical symptoms, but infection may impact performance and make them more susceptible to other diseases.

- Tapeworms may also be diagnosed using a saliva or blood test.

Parascaris (Equine)

- From the ascarid family, these large white worms are prolific breeders, with females able to produce thousands of eggs per day.

- Ascarid eggs are large, dark brown, and have thick-shelled walls.

- Foals and youngsters are the most at risk, but animals can acquire immunity with exposure.

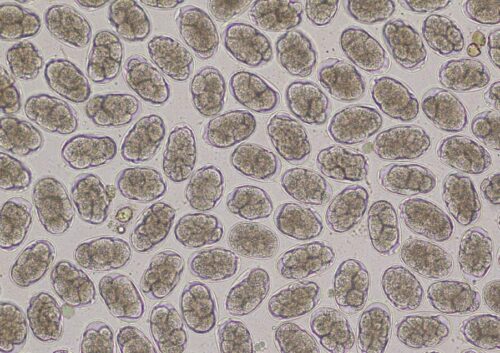

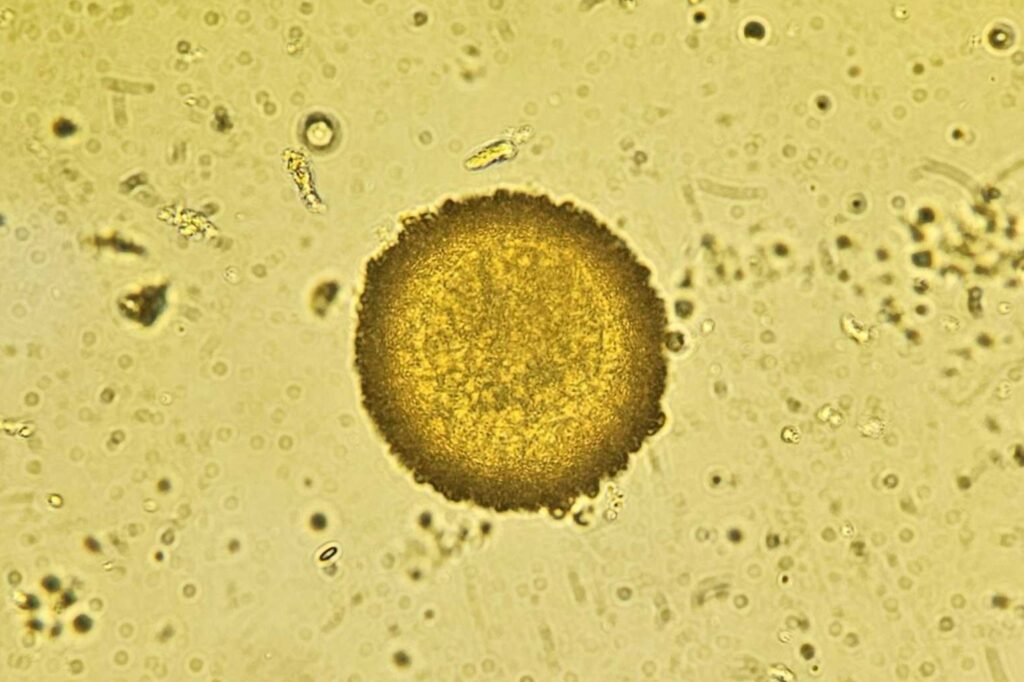

Coccidia

- Coccidia are protozoal parasites, which release infective oocysts into the environment.

- Warmth, moisture, and high stocking densities are risk factors for infection.

- Clinical disease often causes watery diarrhoea with abdominal pain and accompanying weight loss.

Burden levels

A burden table can be a useful tool to help put your EPG result in context. Threshold values are used to categorise the EPG count as ‘light’, ‘moderate’, ‘high’ or ‘very high’ for the different parasites diagnosed with the Micron Kit. EPG counts for each group of parasites are given separately in your report as opposed to an overall egg total, as some parasites are more prolific egg-shedders than others and may be more clinically significant. As previously noted, strongyles are grouped together in the report tables as they cannot be differentiated by visual examination alone.

Coccidia burden levels are slightly different; these are reported as low, medium, high, and very high without a numerical value. Several species of coccidia are capable of infecting grazing ruminants but not all of them are highly pathogenic, meaning some animals may shed high numbers of oocyst in faeces without showing symptoms of clinical disease.

Interpretation of the result should not be based on threshold tables alone. They must always be done in conjunction with knowledge of clinical symptoms present, environmental conditions, life-stage, and immune status of the animal in question. For example, relaxation of immunity in ewes during lambing may lead to large numbers of eggs shed in the faeces but may not require treatment in every case.

It is important to understand a negative result does not mean your animal is free from infection; some parasites only shed eggs intermittently or may not have yet reached maturity. Finally, a faecal test only provides information on the egg levels in faeces at the time of sampling. Regular testing is needed to effectively monitor for parasites.

Click here to request copies our full FEC interpretation guides, with typical symptoms and burden levels for different parasite species.

Ask your vet

If you need any further support understanding your test results, please contact our customer support team. Any concerns about the health of your animals should always be discussed with your veterinarian.

References & useful resources