Neosporosis and Dogs on Farms

Why Dog Poo Can Lead to One of The Most Common Causes of Miscarriages in Cattle…

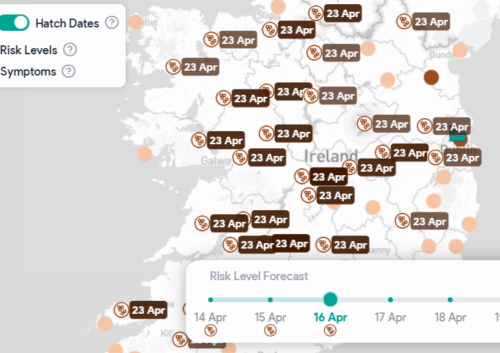

Neosporosis is a widely recognised reproductive disease of cattle worldwide and is one of the most common causes of bovine miscarriage in Irish herds, accounting for approximately 12.5% according to most studies. Previously misdiagnosed as Toxoplasmosis, a disease predominantly associated with miscariages in sheep, the causative agent of neosporosis is Neospora caninum, a small protozoan parasite which affects a cow for the entirety of its life once infection is established. Though adult animals appear relatively unaffected by Neospora infection, the parasite can invade a pregnant uterus and causes spontaneous abortion depending on the stage of pregnancy at the time of infection, leading to financially and emotionally devastating ‘abortion storms’ in the most unfortunate situations. To think that such destruction could be caused over a little bit of ‘dog poo’ seems unreasonable, however, our four-legged, waggy-tailed friends are the sole means of introducing this disease to a herd in this part of the world.

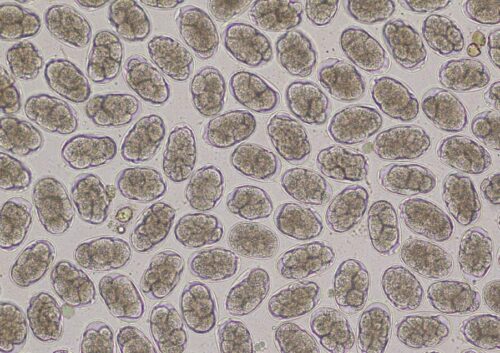

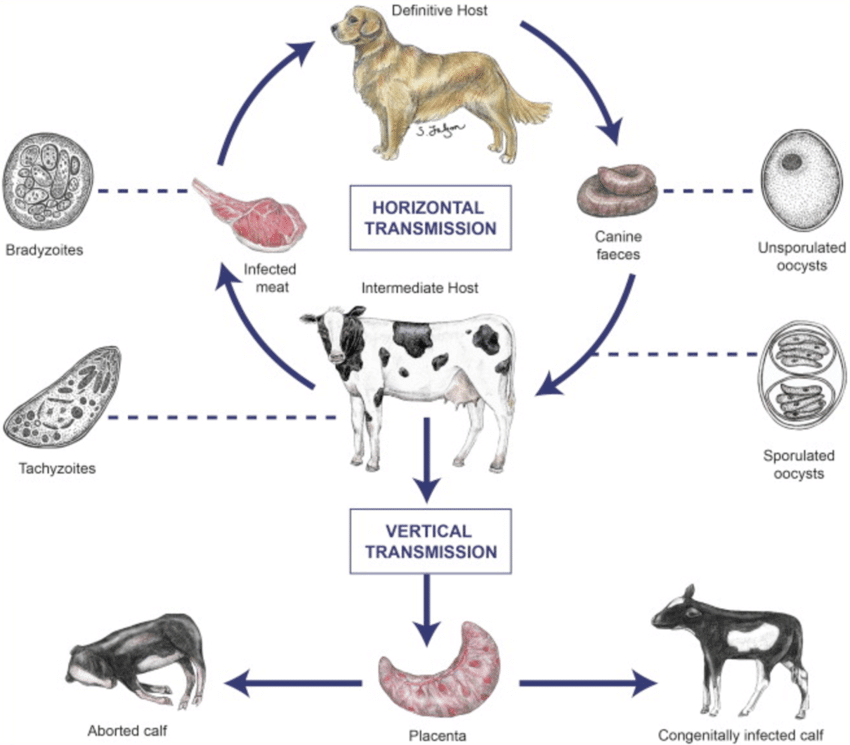

Dogs are considered to be ‘definitive’ or ‘final’ hosts of Neospora caninum, meaning that they pass environmentally-resistant oocysts (eggs) in their faeces that will go on to infect any animal that comes along and ingests it. Cattle, along with many other mammals and birds, are considered ‘intermediate hosts’, meaning that they are a necessary part of the parasite’s life cycle, but do not facilitate the sexual maturity and reproduction of the parasite like dogs do. Inside the intestines of the intermediate host, the parasite is set free and invades many of the body’s organs and tissues; including the reproductive tract, the central nervous system, muscle, liver, and lung. Once settled, the parasite forms thick-walled ‘tissue cysts’, predominantly in the brain and muscle tissue of adult animals, that allow it to lie undisturbed within its host.

If the animal is pregnant at the time of infection, the parasite can travel to the uterus and placenta and will cause destruction of both the maternal and fetal tissues. – If the calf is in its first trimester (i.e. < 100 days since the beginning of pregnancy), it is particularly immunocompromised and infection with Neospora will result in the immediate death of the fetus.

– During the second trimester (i.e. 100 – 150 days since the beginning of pregnancy), the calf has a more effective immune system, but it is currently speculated that the stress of the inflammatory response initiated by the cow in response to the parasite is a major contributing factor in abortion at this stage. Most abortions occur during this time.

– From 150 days onwards, the fetus has an increasingly competent defence system against the parasite, and abortion will generally not occur. However, these calves will be persistently infected for the rest of their lives.

If a dog ingests any Neospora-infected aborted material or raw meat that contains Neospora tissue cysts, the parasites reproduce inside the dog and release the oocysts that start the life cycle of the parasite all over again. This type of infection life cycle is considered ‘horizontal transmission’.

There is a second method of infection with Neospora called ‘vertical transmission’ which occurs when persistently infected animals, namely those as described above which were infected in-utero after 150 days of gestation, spread the infection to their own calves once they reach breeding age. This is because tissue cysts lying dormant inside of these now-adult animals have the ability to reawaken once pregnancy is established, due to pregnancy reducing the integrity of the mother’s immune system, and release parasites that will travel to the reproductive organs in just the same way as for ‘horizontal transmission’. Pregnancies from these persistently infected animals may result in;

– Abortion.

– Birth of weak, underweight, congenitally infected calves that may or may not survive

– Birth of perfectly healthy, but congenitally infected calves.

– Birth of perfectly healthy, non-infected calves.

(Bulls are incapable of spreading infection).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is achieved through tests on blood taken from cows that have aborted and also laboratory examination of aborted materials to look for evidence of infected tissues. There is also a bulk milk tank antibody test available for whole herd screening.

There used to be a vaccine commercially available to farmers aimed at preventing neosporosis but it was withdrawn from the market after showing low efficacy against vertical transmission. There are no drugs currently licensed for the treatment of neosporosis in cattle. Therefore, prevention of infection is the most important means of preventing an outbreak on your farm.

– Resist the temptation to feed raw meat to dogs as this may act as a source of tissue cysts.

– Do not allow dogs access to aborted materials.

– Ensure that feed and water supplies are designed to minimise the risk of possible contamination with dog poo.

– Don’t breed from infected dogs (dogs can pass the parasites onto their pups in just the same way cows can). A blood test can diagnose infection in your dog.

– Consider culling cows that are affected in any capacity.

– Maintain biosecurity as much as possible, limiting the number of animals bought in and only buying from ‘known disease status’ herds.

Also, if you yourself are an avid dog-walker or have friends or family who are, please be aware of the risks associated with allowing your animals to defecate freely on farmland when out on adventures. The consequences could be far more severe than just a ruined shoe sole!