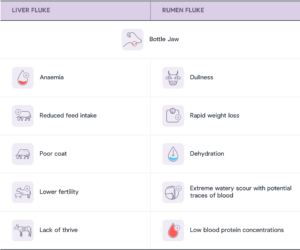

Liver fluke is an economically important parasitic disease of grazing animals caused by the flatworm Fasciola hepatica. Liver fluke disease is estimated to accumulate around €2.5 billion in costs to livestock and food industries globally, including an estimated cost of €90 million to the Irish industry [1]. Symptoms of liver fluke infection include bottle jaw, reduced feed intake, lowered fertility, lack of thrive, and poor coat (see Table 1) [1,2]. These infections can be chronic and can cause anaemia under heavy parasite burden [2].

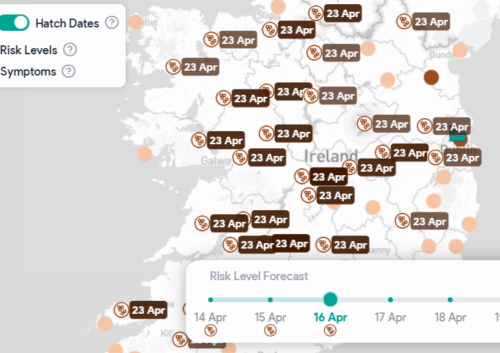

Liver fluke infection can be acquired all year round by cattle, sheep, and even horses [4], however, most infections typically occur in winter after animals have grazed on fluke contaminated pasture from summer and autumn. Liver fluke infections are driven by weather patterns and changing climatic conditions that affect infection pressure year on year. An annual risk forecast of liver fluke infection is provided by The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) [5]. The 2023/24 forecast indicates a high risk across Ireland, except for moderate risk in south Leinster. The high risk is associated with mild temperatures and above average rainfall that provide optimum conditions for the development of fluke [6]. 2023 saw the warmest year on record in Ireland with an annual average temperature of >11°C [7]. There were unprecedented levels of rainfall at times of the year, with March and July being the wettest ever on record [7]. This progression of an increasingly mild and wet Irish climate, spanning for a greater period of the year, will only come at the cost of an unpredictable increase in parasite prevalence by generating extensive favourable conditions for fluke development.

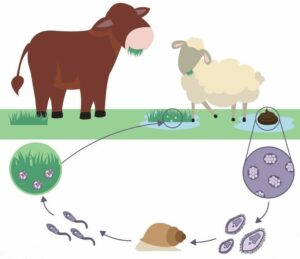

Wet summers are ideal for supporting the fluke life cycle as it provides the intermediate host, the mud snail, with an ideal habitat (see Figure 1) [8]. These mud snails can also hibernate over winter, therefore delaying the infection and allowing animals to become infected in the spring. Clinical signs of infection should be routinely monitored and diagnostic testing should be conducted to evaluate both subclinical and clinical infections [1]. Treatment decisions should also be tailored to each individual farm while remaining highly vigilant of wetter, muddy or ‘flukey’ areas of the farm. When treating, avoid combination wormers/flukicides unless necessary and consider regularly rotating drug actives as inessential use can increase resistance to the medication [2].

All parasite control measures should be discussed with a vet/animal health advisor and if treatment is required, ensure you follow the 5’RS:

Rumen fluke, caused primarily by Calicophoron daubneyi, is considered a common parasite of the rumen in sheep and cattle, having increased in prevalence over the past few years [3]. This parasite has rarely been associated with fatal cases and the adult stage is generally not considered to cause disease. Clinical manifestation occurs in animals when rumen fluke larvae migrate in great numbers in the intestine. Clinical signs of infection include bottle jaw, dullness, dehydration, rapid weight loss, extreme watery scour, and low blood protein concentrations (see Table 1) [3]. When suspecting a rumen fluke infection, it is best to consider and rule out the presence of other parasitic infections, such as liver fluke, before considering treatment. The majority of drug activities for liver fluke do not treat rumen fluke. Treatment should only be considered when losses have been confirmed through post mortem as this provides absolute evidence of severe rumen fluke infection. Blood sampling may also be necessary to confirm blood proteins associated with rumen fluke infection. Best practice for controlling rumen fluke would be to reduce the animal’s exposure to acquiring the flukes by draining and fencing off wet areas of the field.

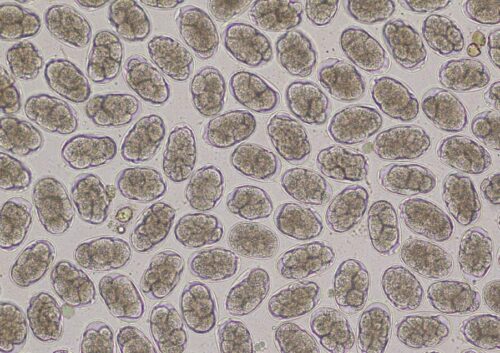

In order to deal with fluke correctly, each liver fluke treatment plan should be tailored for each specific farm, including farm history data and clinical signs. Epidemiological data and liver fluke forecast announcements should be regularly tracked to understand regional and local fluke infection risk [5]. With greater variation in weather patterns, regular testing can help you with diagnosing fluke in susceptible animals. As there is a year-round risk of infection, conduct regular testing to routinely monitor for fluke eggs using Micron Kit +Fluke throughout the year and to assess the efficacy of your drug active if administered treatment for a confirmed positive infection. Remember, by testing regularly you are prioritising the health of your animals by ensuring the right animal is getting the right product at the right dose rate and time to be administered in the right way.