Strike; you’re out!; Blowfly strike in sheep

Let’s face it; very few people can say they’re excited when the warmer weather starts rolling in and the flies start appearing as if out of nowhere. When they’re not landing in your food or keeping you awake at night with incessant buzzing and bumping into windows, it’s sometimes difficult to imagine these little winged creatures as having a personal agenda other than simply annoying the human race! However, the next time you’re running around protecting your pint or picnic, thank your lucky stars that you’ve got the arms to do so! Unfortunately, our poor sheep friends don’t have that luxury…

(* Disclaimer: maybe it’s best to read this article AFTER you’ve finished your breakfast! *)

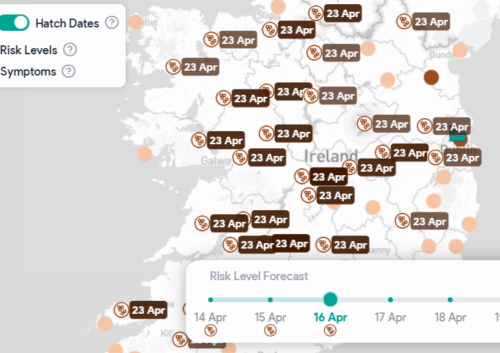

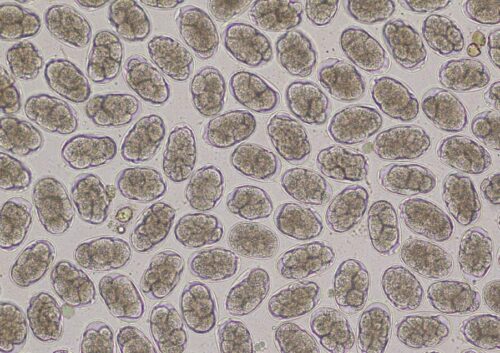

Blowfly strike, or ‘facultative myiasis’ as it is more formally known, involves female flies feeding on and laying eggs in the wounds and dirty coats of warm-blooded animals; ‘blow’ refers to the deposition of eggs on the animal and ‘strike’ referring to the damage caused by the larvae that develop from these eggs. Sheep are the most commonly affected animals by this phenomenon due to their thick fleeces, though it is also becoming a more widely recognized problem in pet rabbits. The female flies, the most common perpetrators being bluebottle, greenbottle and blackbottle flies, feed on liquid protein or the nectar of certain plants before laying their eggs on open wounds, soiled fleeces or dead animals. One protein meal can allow a single female fly to produce over 3000 eggs over her 30-day lifespan! These eggs will hatch within 12 hours of being laid and reach maturity within 10 days while feeding on their chosen host. Once mature, they drop off the animal onto the ground to form a pupa, similar to a butterfly’s cocoon, that will hatch into an adult within 3-7 days or overwinter and hatch the following year, depending on environmental conditions. Up to four generations of flies can exist between May to September because of their short and effective life cycle, so it’s easy to see how a ‘fly problem’ can quickly become a big one!

Blowfly larvae, or ‘maggots’, are usually more commonly associated with death and decay. However, some strains of flies prefer their young to feed on live animals. The larvae secrete (or spit out) an enzyme that degrades and liquefies the wool and skin of the sheep, causing smelly, wet, painful lesions at the feeding site. This smell of decomposition attracts more flies to the area, which results in more eggs being laid and more larvae that need feeding, so the problem spirals out of control quite quickly. Affected sheep are generally irritated and distressed, often losing considerable weight as they are more preoccupied with itchiness and pain than with eating. Secondary bacterial infections can occur in these open wounds, which can have fatal consequences. Approximately 10% of sheep affected by blowfly strikes will die from their infestations.

Predisposing factors for strike in sheep revolve mainly around moisture and general fleece hygiene:

- When fleeces are wet, bacteria can cause the wool to degrade and sometimes the most superficial, or uppermost, layers of the skin will degrade with it; this is known as “fleece rot”. The foul odour associated with this will attract flies. Therefore, high levels of rainfall and humidity are important factors to consider when assessing risk in your flock.

- High temperatures will affect the microclimate of the sheep’s fleece and influence the hatching of any overwintered pupae on the ground from the previous year. This directly impacts the severity and number of incidences of strike in a particular area (normally seasonally from July to September). Flies are also more active in warmer weather as they are ectothermic or “cold-blooded” creatures that rely on the temperature of their environment to control their own body temperature and, therefore, energy output.

- Dirty fleeces, namely their smell, are probably the biggest culprit in attracting blowflies. The most common sites for sheep to be affected by strike are their breech (buttocks) and around their tail, where the wool is easily soiled and stained by faeces and urine (in the case of female sheep). Wounds caused by shearing, fighting, tail-docking or castration in male lambs can also serve as wool contamination and attractiveness sources for flies.

Flystrike should be suspected in any animals that have characteristic grey-black discolouration of their wool, look uneasy in the field (twitching of their lips, stamping of the hind feet and rapid swishing of the tail) or emanate the putrid odour associated with maggot infestation. Treatment can be achieved by removing larvae from the animal’s wounds and treating them with a suitable insecticide.

To prevent blowfly strike in sheep:

- Treat any injuries with insect repellent.

- Strategize a good anthelmintic plan with your vet that will control gut worm burdens and minimize the incidence of diarrhoea in your flock.

- Remove excess wool from the groin area of sheep to reduce the buildup of soilage.

- Shearing sheep before high-risk periods begin ensures that the eggs will not have any wool to stick to, and the larvae will have limited protection from the elements.

- Selectively breed your animals to incorporate individuals more resistant to strike than others (yes, this is possible; genetics are amazing!).

- Dispose of any waste material or dead animals safely and effectively away from where the flock is grazed.

- Sheep should be prophylactically treated (i.e. treated before disease strikes) with an insecticide with residual activity. This means that the medication will stay active and effective on the sheep for a long time if applied correctly. Best results are achieved if the wool is 2-3cm in length and the treatment is bound to the wool fat (an oily substance obtained from wool that gives it its ability to absorb and hold water). These insecticides can be applied using a hand spray, a jet or a dipping bath in June and August. Sheep that are dipped must be immersed in the liquid for a minimum of 60 seconds. Cypermethrin treatment will provide up to 8 weeks of protection against strike.

- Insect growth regulators (IGRs) work by interfering with the development of the blowfly larvae, preventing them from feeding. This means that these products will only work before the incidence of strike as they have no effect on already hatched larvae! When used correctly, these products (the active component being cyromazine), administered as a pour-on treatment, provide up to two months of protection.

More extreme measures of protection may have to be implemented in the coming years due to the increased incidence of resistance to some of these insecticides in certain species of flies.

- Vaccination of susceptible sheep was experimentally trialled in Australia and resulted in smaller blowfly larvae due to affected growth rates. Research is still ongoing in this area as there are many barriers to overcome, but the outcome looks promising.

- Chemically sterilized flies can be released into an area that will pass on this sterilization to any other untreated flies they mate with. Studies suggest that up to 95% reduction in fly populations in a given area can occur after treatment of 5% of the flies.

- Even the concept of releasing parasitoid wasps into an area to bring down fly populations has been attempted (though I’m personally a fan of leaving this one as a ‘last case scenario’!)

This article doesn’t, and shouldn’t, serve as a message to kill every fly you see from this point forward! Flies are actually quite an essential component of the earth’s ecosystem; pollinating plants with their hairy legs and bodies (blowflies can carry more pollen on their bodies than honey bees!), acting as a food source for other animals, and breaking down all of the disgusting waste left in the environment that would otherwise be expected to go for landfill. Sheep blowfly larvae are even used to treat diabetic ulcers, bedsores and other chronically infected wounds in human patients; eating the dead tissue, cleansing the wound with antibacterial properties in their saliva and speeding up the growth of new healthy tissue. So the next time you’ve got a bumbling, buzzing nuisance in your living room and you’re considering reaching for the rolled-up newspaper, maybe reassess. Have a chat about the looming prospect of parasitoid wasps taking over the world before you set them free, and they might change their ways (I know it’d do the trick for me!).