Everything you need to know about Liver Fluke.

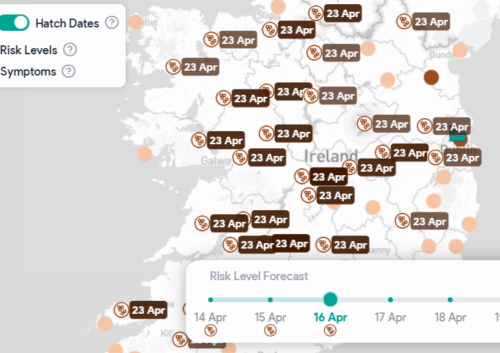

Fasciola Hepatica or Liver Fluke as they are more commonly known, are whitish-brown flat worms that reach around 3cm when fully mature. Resembling leaves in appearance, they use a muscular pharynx to ingest the host liver tissue before becoming fully mature. Adults can be found in the bile duct of the host liver eventually producing large golden-brown eggs which infect pasture. Flukes can cause significant impact on the health and production of grazing ruminants – particularly when climate conditions are favourable. They have a complicated life cycle with different stages involving an intermediate and definitive host interspersed with short free-living interludes. As fluke rely on contact with aquatic snails for early stages of replication the parasite is largely found on land with damp areas prone to flooding, although generally they thrive in mild and moist climates. Whilst traditionally this limited their geographical spread, they are now being identified increasingly further afield. In sheep for example, incidence is increasing in flocks further North and East than seen in previous years – which may be linked to the effects of climate change. Whilst grazing ruminants are the primary concern for farmers, wildlife may also act as a reservoir and must be considered in control plans.

Life cycle

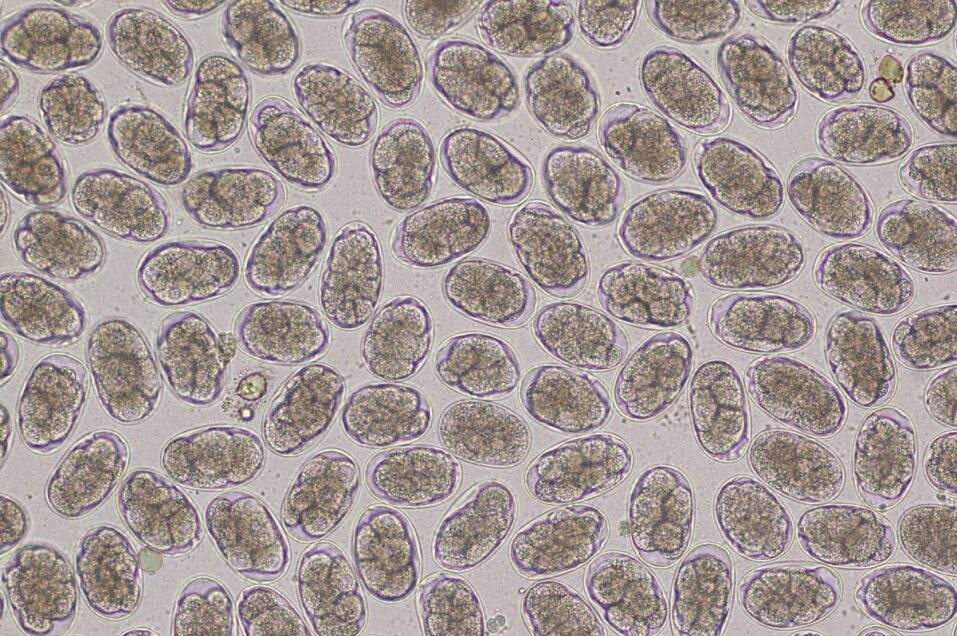

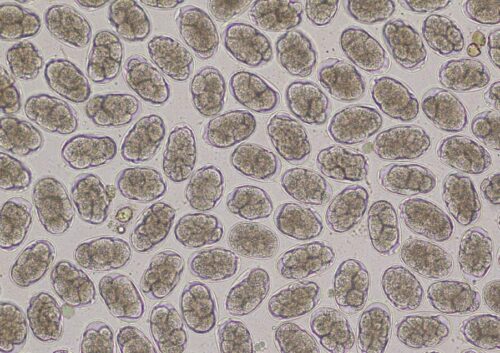

Flukes are hermaphrodite, containing both male and female reproductive organs. Adults in the host bile duct produce eggs which travel through the gut and eventually pass out with faeces onto the pasture. Each egg contains an embryo, which continues to develop until hatching into a conical shaped larvae – a miracidia.

Miracidia on the pasture are vulnerable and need moist conditions to survive. In a race against time, they must locate a host within three hours to avoid perishing. Using a rotating action, they can move in bodies of water searching for the mud snail Lymnaea Truncatula. Once a suitable snail has been encountered, they bore into the snail tissues and transform into a sporocyst. The developing sporocyst continues to grow within the snail and forms several separate rediae within the original cyst. These eventually break out to move freely within the host snail to feed. At the end of this stage, the rediae will transform into a new stage ready for leaving the snail – the cercaria.

With a spherical shape and un-forked tail, the cercaria are well suited to life outside of the snail. Once leaving their intermediary host, they swim through the water and eventually attach themselves to a blade of grass or submerged vegetation to await the encounter with their final host. Shedding their tails, they once again become encysted for protection and become a metacercaria. Grazing animals will crop the grass and vegetation, ingesting the encysted parasites and facilitating their transport into the gastrointestinal tract of the new host.

Metacercaria excyst in the host duodenum and find their way to the peritoneum before locating the surface of the liver. Here, they will burrow into the tissue to feed and grow as juveniles for around 6-8 weeks before migrating to the bile ducts. Here, they will spend a further 4 weeks in their adult form, eventually producing eggs which travel through the bile and through the digestive tract to pass out with the faeces and begin the life cycle again. Burden level within each animal is dependent on the amount of metacercaria that were ingested, and some animals may have such large numbers of adult worms that risk of bile duct obstruction becomes significant.

Clinical Disease

Clinical disease symptoms in host animals occur on a spectrum, with severity dependent on both the burden of the parasite and the condition of the animal prior to infection. Fascioliasis can cause significant production losses affecting milk, meat and wool output. An increased incidence of liver condemnation at slaughter may also be observed. Generally, sheep are more severely affected than cattle due to their relative size difference but the overall health of the animal, parasite burden level and treatment regimes in place will have a significant impact on the level of clinical disease seen.

In sheep for example, acute disease is often associated with anaemia or may be diagnosed following investigation of a sudden death – usually occurring between August and October. If a post-mortem follows, evidence of liver damage and associated haemorrhage from large numbers of fluke migrating through the organ can often be found. Whilst acute disease does occur in cattle, it is rare. Subacute fascioliasis causes a range of clinical signs generally seen as ‘failure to thrive’ and ‘poor doer’ in the herd or flock. Loss of body condition, poor fleece quality, colic and depression are vague symptoms and generally alert a farmer that something is going wrong; however, investigation will be needed to diagnose fluke. Death in the subacute category is most likely to occur in the winter. Chronic sufferers generally have a very poor body or fleece condition, chronic scour, and may exhibit signs of ‘bottle jaw’ or brisket oedema. Death may also occur in chronically diseased sheep during lambing.

Infection with fluke also puts individuals at risk of suffering secondary complications. Physical damage to the liver as the worms feed can leave cattle and sheep vulnerable to Black’s disease (infectious necrotic hepatitis). As the parasite ingests the host tissue, pockets of necrosis begin to form. Clostridium Novyi, a bacteria found in soil may be ingested by cattle and sheep as they graze. Whilst not pathogenic when in an oxygen rich environment, in the areas where necrosis is present the bacterium may begin to produce toxins. These cause further damage to the liver and often result in sudden death. Post-mortem changes can reveal the tell-tale blackened areas with likely identification of juvenile fluke present. Furthermore, there have been reported links between subclinical fascioliasis in cattle and Salmonella Dublin infection.

Diagnosis

Once liver fluke can be identified, a farmer and their vet can work together to tackle the problem. Whilst clinical symptoms can be suggestive, testing is needed to confirm the presence of the parasite. Blood tests showing elevated liver parameters will further aid suspicions and a veterinary surgeon will most likely recommend a more specific diagnostic test.

ELISA antibody testing is a popular choice and can be used to test blood samples from individuals. Whilst a positive result will confirm there has been fluke exposure, there is no way to know if this was a recent or historic infection. A second approach is to run this test on a bulk milk tank sample. A positive result in this case is helpful to identify exposure, but there is no way to be sure which individuals are affected, or if the whole herd have been exposed to this parasite. An ELISA test can also be run on a faecal sample to detect immature fluke not yet producing eggs – however this will require a specialised laboratory to process the samples.

Faecal egg testing will detect the presence of the eggs in faeces, but only if there are adult worms at the right life stage to produce eggs. Remember – ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence!’ so regular testing is the way forward.

Work is under way at Micron to develop a reliable and cost-effective test for pen-side use that allows detection of fluke eggs compatible with the existing kit, so watch this space!